Bishnoi, renowned as the “India’s first environmentalists”, is a Hindu sect found in Western Thar desert, Rajasthan, and northern parts of India. The name Bishnoi (bish means twenty, noi means nine) has its roots coming from the 29 tenets put forth by their prophet, Guru Jhambheshwar (born 1451). He belonged to the higher ranks of the society by being a Khastriya, the second highest at the caste system. However, he made an unprecedented move to abolish the caste system altogether. The impact of this commendable move has continued ever since.

Guru Jhambheshwar advocated the protection of trees and wildlife. He prophesied that harming the environment means harming oneself. His 29 tenets include a ban on killing animals and felling green trees and providing protection to all life forms. The community is also directed to be careful about the firewood they use, which should be devoid of small insects.

The tenets proposed demands great care for nature. Any form of activity that results in harming the environment is banned outright. Of the 29 tenets, ten are related to personal hygiene and maintaining good basic health. Seven of them are about healthy social behavior and five tenets about the worship of God.

The Bishnois are directed to have pity to all forms of living beings and to love them. Animals such as goats and sheep are provided a common shelter to avoid them being slaughtered or attacked by wild animals. Also, the community is directed to see that the firewood they use is devoid of small insects. Furthermore, wearing blue clothes is prohibited because the dye for coloring them is obtained by cutting a large number of shrubs.

The equal appearance of the people remained the cornerstone of his principles. This policy of uniformity among people was imposed mainly to prevent jealousy and to promote peace. As a result of this, all women wear very bright, predominantly red saris of patterned cloth and adorn themselves with nose rings, bracelets, and anklets. Men wear basic white clothes representing simplicity and modesty.

A Question Of Survival

The harsh climatic conditions pose a constant threat of drought. Therefore, the Bishnois have to adopt proactive agricultural development. The food reserves stacked can feed a family up to two years.

Despite the unpropitious arid climate conditions, Bishnois have no compromises for food they eat. During the monsoon season, they grow millet, which is then ground into flour for their staple food, chapattis. Sangari, a bean-like fruit of the khejadi tree, is dried and mixed with the berry of the kair, a desert bush. Chapattis, sangari and kair berries are the staples at most meals. They are frequently supplemented with butter and yogurt, which are delicacies from the few cows that Bishnoi families raise.

The monsoon season of India, July and August, usually brings rain to the Rajasthan Thar desert. In a good year, the harvest season extends through October. However, due to the inherent harsh and unforgiving climate, being well aware of the prescient warnings of drought can be vital for their survival. For the very same reason, Guru Jhambheshwar propounded a proactive approach to agricultural development. They need to plan far ahead to survive on their reserves of food and water. Typically, the reserves that are stacked will feed a family for up to two years. Thus, the Bishnois are well-prepared for unforeseen circumstances.

Time after time, Bishnois have adhered to the stringent principles even when they are tested severely. Vegetation, fuel, and the other materials required to build a place to live are all scarce in this region. Instead of cutting living trees, they rely entirely on dry, dead wood. Much of fuel for cooking comes from dried cow and water buffalo dung. In fact, Bishnois bury their dead instead of cremating to avoid cutting of trees.

The Khejarli Massacre

When the Jodhpur king wanted to build a new palace, he enjoined the soldiers to cut trees in the Khejarli region. The local villagers staged a non-violent protest and shielded the trees by offering their own body.

The principles laid by Guru Jhambheshwar have had a profound effect for many years, and they are impeccably followed by the Bishnois. The Khejarli Massacre (forebear of Chipko movement) event is one such typical example. In 1730, the Jodhpur king required wood for the construction of his new palace. Hence, he enjoined his soldiers to cut trees found in the nearby regions of Khejarli.

When the local villagers learned about the circumstances, they staged a non-violent protest by shielding the trees. The king’s men were intransigent and offered money as a bribe. Amrita Devi, a plucky Bishnoi woman, said that she would rather give away her life to save a Khejarli tree. These baleful incidents eventually lead to the death of more than 363 other Bishnois. Having learned about the great sacrifices being made, the king halted the logging. He also asserted that the Khejarli region would be preserved eventually banning logging and hunting of animals. The sacrifice of Amrita Devi is still remembered as the great Khejarli sacrifice.

Today, as a token of appreciation, the award “Amrita Devi Bishnoi Wildlife Protection Award” is presented by The Ministry of Environment and Forest in India. The award is given to individuals and community-based organizations for having done exceptional work for the protection of wildlife.

A Unique Blend Of Love And Compassion

Bishnoi people treat the animals in the region as their own family members. Specifically, blackbucks (or Indian antelopes) are revered the most as Bishnois consider them to be their reincarnated dead ancestors.

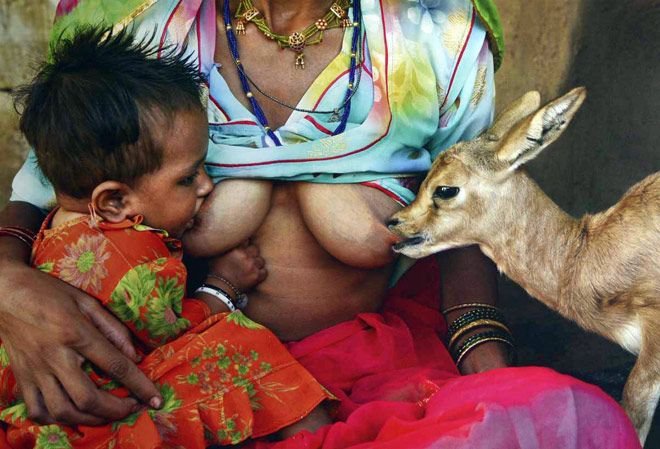

The Bishnois’ love for animals and trees knows no bounds. The animals around the region are treated as their own offspring. Antelopes, especially, are respected the most because they are believed to be the reincarnation of their dead ancestors. Moreover, before the death of Guru Jhambheshwar, he had stated that blackbuck would be his manifestation after death. The following is an excerpt from MailOnline’s interview with Mangi Devi Bishnoi (age 45), a housewife from one of the villages.

“These baby deers are my life and they’re like my own children. I feed them milk and food and ensure that they’re given proper care and attention in the house like all my family members.”

The eminent worshippers consider animals in the region as members of their family. According to them, there is no distinction between humans and animals. These people evoke a feeling of oneness among all the diversities because they are used to playing with different kinds of animals. It couldn’t get any better since they even communicate with animals. The following is an excerpt from MailOnline’s interview with Roshini Bishnoi (age 21), a student in one of the villages.

“I have grown up with these little deers. They’re like my brother or sister. It is our responsibility to keep them healthy and help them grow. We play with them and we communicate with each other, they understand our language.”

Conclusion

A Huge Takeaway

As a result, the sect has prevailed over all the odds for 550 years now. The halcyon days are still prevalent suggesting that the legacy of Guru Jhambheshwar has been continued successfully. Love, compassion, and unconditional empathy for nature is constantly increasing, making them the epitome of humanity and epitome of altruism. For sure, the Bishnois have a big message to the world. Spread these words.

Footnotes :

- Sources : nativeplanet.org, dailymail.co.uk, envfor.nic.in, wikipedia.com, bishnoism.com

- In October, 1996, Nihal Chand Bishnoi sacrificed his life for protecting wild animals. A film, “Willing to Sacrifice”, based on his story won the award for the Best Environment Film at the 5th International Festival of Films, TV, and Video Programmes held in Bratislava, Slovakia.

No comments:

Post a Comment